The above is my first ever documentary film called "Tribes and Trance". A lot went on behind the camera that was also part of my experience and that I feel the need to reflect upon here...

Let me start off by saying that Tribal Gathering is a beautiful festival, and although my film looks at the event from a critical perspective at times, it really is one of the most unique festivals in the world.  The indigenous aspect, plus the fact that it is almost three weeks long, really sets it apart. If you have any interest in transformational festivals, psychedelic culture, or festival culture in general, it should definitely be at the top of your list. And even if you don't have much interest in these, I think it's a very valuable experience for anyone wanting to expand their mind.

The indigenous aspect, plus the fact that it is almost three weeks long, really sets it apart. If you have any interest in transformational festivals, psychedelic culture, or festival culture in general, it should definitely be at the top of your list. And even if you don't have much interest in these, I think it's a very valuable experience for anyone wanting to expand their mind.

I was extremely nervous going into this festival because I knew I would have to “find” the story and characters for my documentary. To do that, there is only so much planning you can do beforehand. I knew I would have to dig deep with people in order to make the film a success.

The Festival Begins

The first couple days nothing actually happens. There is no schedule of events, it is purely so attendees can arrive and acclimatize at ease. Unfortunately for me, I spent these days running around figuring out how the hell I would film there for the next 3 weeks. The organizers were nowhere to be found, I had nowhere to leave my gear, nowhere to charge my gear, no one knew what I was there to do, I was sent in circles many times… it was frustrating.

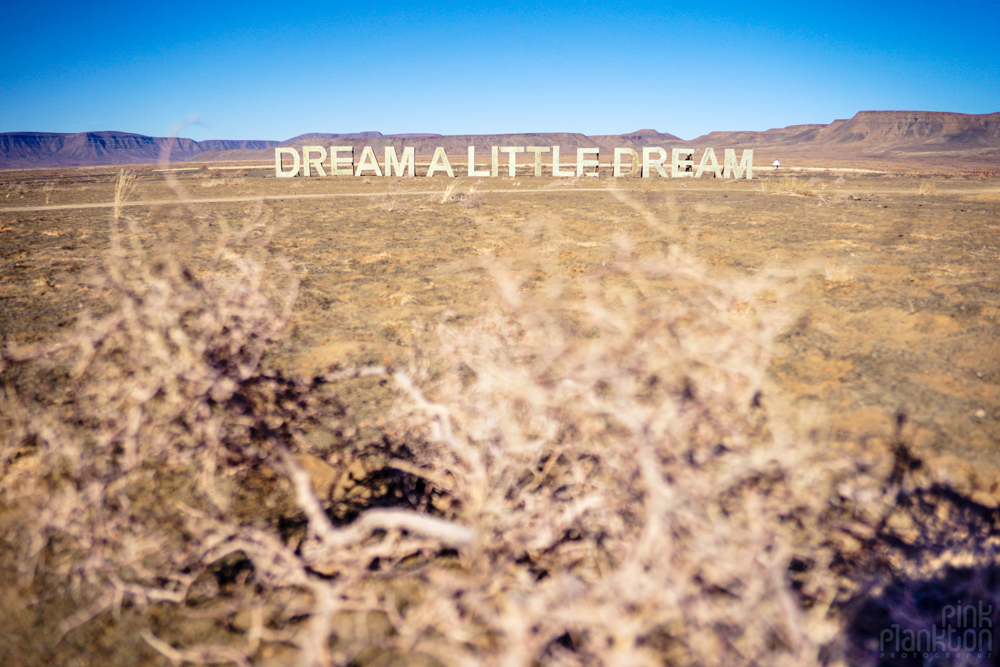

Eventually, I sorted all this out. The first day of the indigenous immersive part of the festival began. I started off by filming a beautiful dream root ceremony put on by the Khoi-Khoi tribe from South Africa. There was a great turnout and the energy was high. I got some wonderful shots, and more importantly, I remembered why I love film and why this was my passion.

Tragedy in Ceremony

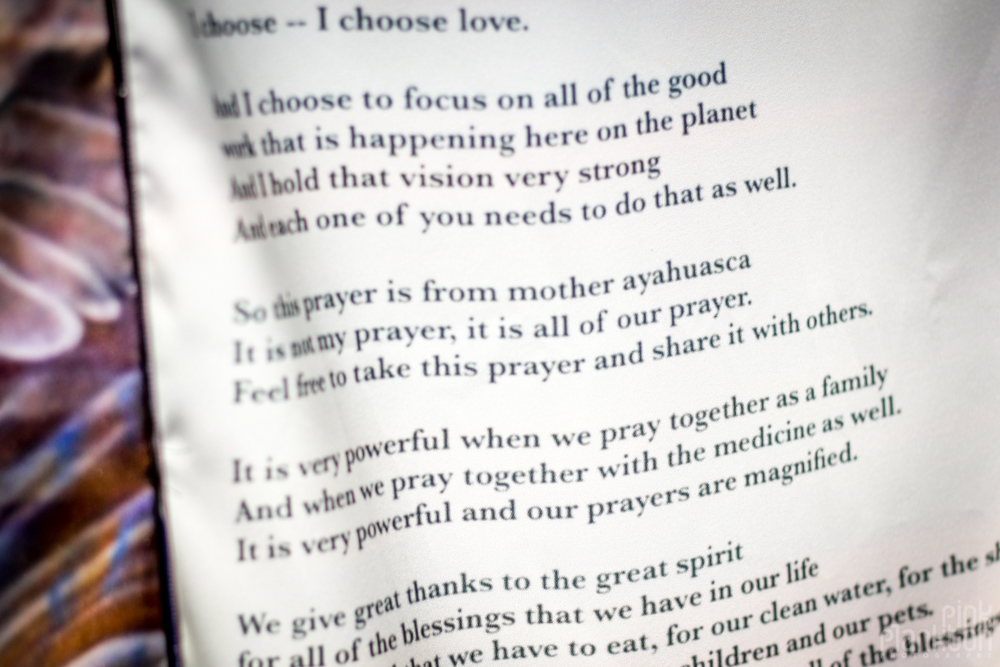

During the indigenous immersive, there are four days of shamanic plant ceremonies. This is another aspect of the festival that makes it quite unique. I was asked not to mention this element in the documentary.

This year, iboga, peyote (mescaline), bufo (5-meo-DMT), and a few others were offered. For many attendees, the opportunity to participate in these ceremonies is a major reason why they come.  This is apparent because every morning during sign up there is a HUGE lineup of people, even an hour before signup opens (it's first come, first served). Each ceremony ranges from $100-$200 USD.

This is apparent because every morning during sign up there is a HUGE lineup of people, even an hour before signup opens (it's first come, first served). Each ceremony ranges from $100-$200 USD.

The morning of day four, news quickly spread that someone had passed away in an iboga ceremony the night before. I never got to meet the man, but my heart goes out to David and his family and friends.

I later learned from someone much more knowledgeable on iboga than I, that it is one of the only psychedelics where participants must have an EKG done beforehand to check for heart irregularities. This is because it acts on your respiratory system. Although the festival organizers did not mention the cause of death, there was no doubt in my, and many others’ minds, that David died of a heart attack or other related complication in ceremony, because this was overlooked.

The plant medicines offered at this festival are very powerful psychedelics and it was obvious that the festival was going about it the wrong way. They simply weren’t able to screen the hundreds of people in line properly. Not to mention a lot of these medicines normally require weeks of preparation, proper diet, etc., beforehand.

Would these shamans normally perform ceremonies for people they barely knew? Would they normally hold ceremonies for a group of 20 people and clearly not enough facilitators?

I'm unsure if this is a fact or not, but I had been told that back in the day, the shamans held ceremonies at the festival on their own terms, and 100% of the money went to them. Now, only 50% of the cost goes to the shaman, while the festival gets the other half.

Although I knew I wouldn’t be able to mention the death, nor the ceremonies in the documentary, this news did raise a few hints to the story that would later unfold…

Critical Thinking

A few days later I had a very meaningful conversation with someone I met who also works in the media industry. He reminded me of the importance of independent media and the importance of what I was doing there. He even went as far as to say that it was my duty and responsibility to report what was actually going on here, because if I didn't, no one else would.

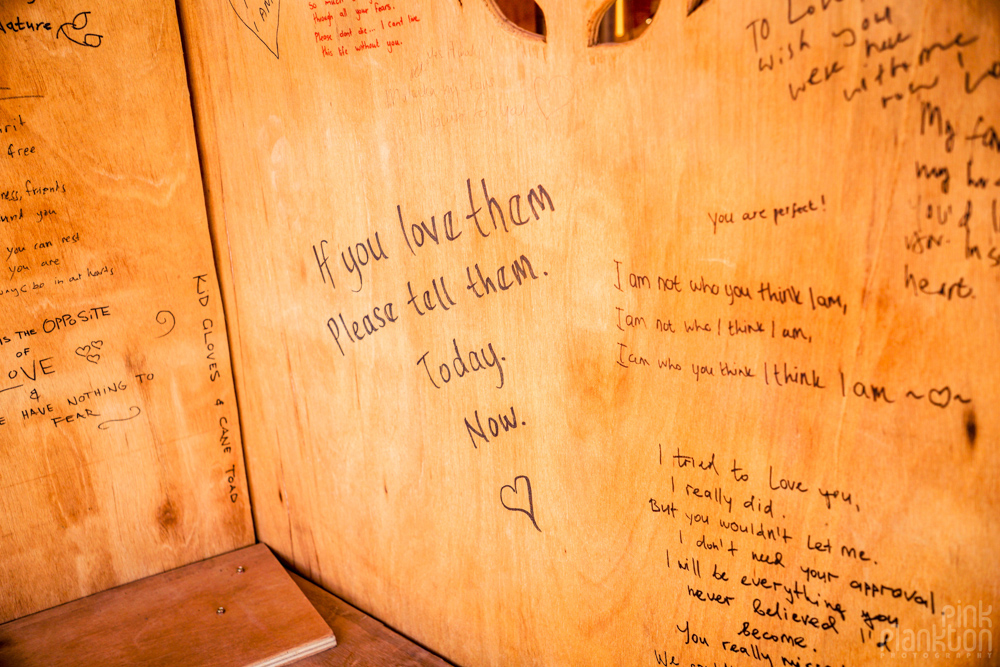

I felt the pressure. I had never really thought of it this way. I came here wanting to shoot a documentary that shows what goes on at these types of "conscious/transformational" festivals. I'd had nothing but positive, sometimes life-changing experiences, at them in the past, and I wanted to show others that there was something more going on at these events than what you'd find at your average Coachella/EDC/other commercial music festival.

But the recent tragedy was what was really going on at this particular festival. Clearly, it wasn't all positive. And this is what people needed to know. I really had to put my own personal experiences with the community aside and focus on telling the story from an outsiders perspective.

I recalled an article by Optimystic Media Hub that I'd stumbled upon years ago. Here, Wesley Wolfbear Pinkham asks, "how independent and critical can we expect outlets to be if they are dependent on playing nice so that they can get tickets to future festivals?" He later asks media outlets to "start writing critically, using the logical mind to identify opportunities for growth, potential pitfalls that could break our momentum and call for honesty, integrity and transparency from festival producers."

Tribal Gathering did not comp my entry into the festival. I had the support of Matador Network (the world's largest independent travel publisher) on this project. These two factors helped allow me to create a piece that examines the event critically, something we need to see more of in the festival media landscape.

The Struggle for Wifi

With all this swirling around in my head, I tried to get on with what I was there to do. Over the next week, my days were filled with capturing as much as I could, while also trying to take time to just be me and to get to know others. It was approaching the end of the first week when I started to really freak out.

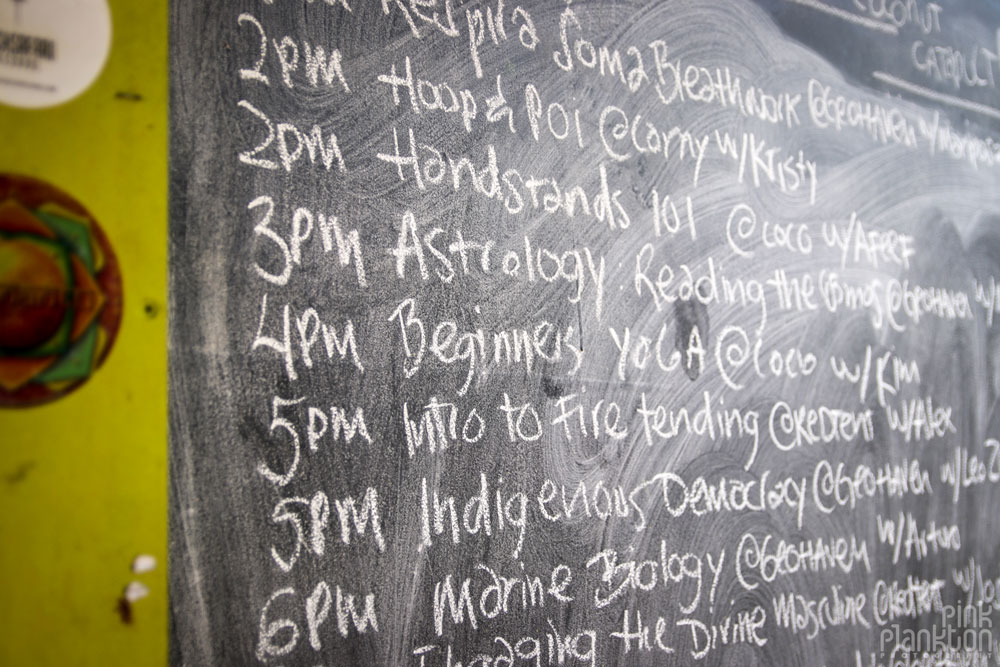

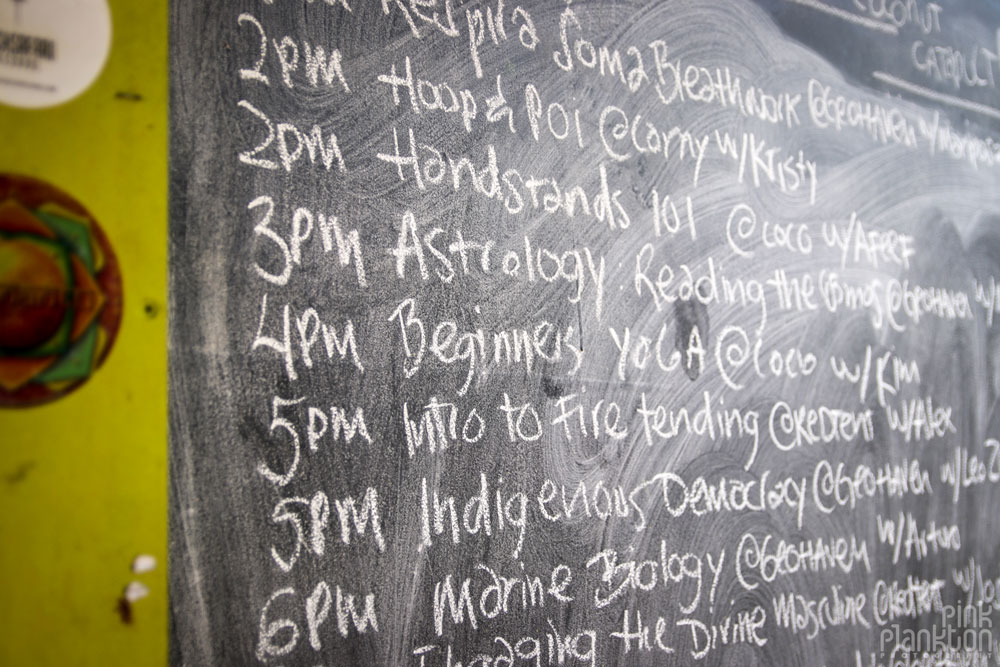

I had a rough plan to focus the doc on a few characters and I realized that this simply wasn’t going to work. Everyone there was on festival time, meaning no time.  It was impossible to know what someone was going to do on any particular day. Even the tribe members didn’t know what date or time their workshops would be held. The schedule for the day’s events was decided the day before (and always up for revisions the day of).

It was impossible to know what someone was going to do on any particular day. Even the tribe members didn’t know what date or time their workshops would be held. The schedule for the day’s events was decided the day before (and always up for revisions the day of).

I so desperately wanted to send an email to my team at Matador Network for guidance but the wifi situation in the middle of the jungle was grim. The festival had pay per use wifi, but of course the first week it wasn’t working. Then they ran out of passwords. Then it wasn’t working again. There was a bit of signal at the end of the beach that I tried with my phone and my friend's phone, but unfortunately couldn’t connect.

I didn’t know how to proceed with the documentary and I knew time was running out. Although the festival lasts 18 days, by the end of the first week, I only had a few more days before the psytrance portion began. They'd begin blasting music 24/7, making it impossible to conduct interviews. Not to mention during this time, people would be much more likely to be in an altered state of mind.

A Different Plane

I remember feeling so stressed, sad, and alone. I felt I was on a different plane than everyone else. I was mainly there for work, while everyone was mainly there to enjoy themselves. This documentary meant so much to me, it is something that I’d been wanting to produce for years, and I was so afraid of failing.

Thankfully, one day when I went to the end of the beach, my camp mate was there and I was able to hotspot and send out an email to my team. The next day the festival’s internet actually worked, and I was able to check for responses.

Immediately I was put at ease. They assured me it was okay to veer off the original plan and instead refocus on the story that was unfolding all along in my talks with people I had been meeting…

The Real Story

I went into Tribal Gathering expecting a very cohesive marriage of the two parts of the festival (the indigenous part and the dance party part).

However, the more I talked to people, the more I realized not everyone felt the cohesiveness. Some were more there for the indigenous part, some were more there for the partying, many were there for a combination of both.

But did they even belong together?

I interviewed 19 people at the festival, and although only 9 made it into the final cut, I am grateful for everyone who took the time to chat with me, both on and off camera. It truly helped give me a rounded perspective and understanding of the meaning of the event.

Psytrance Time

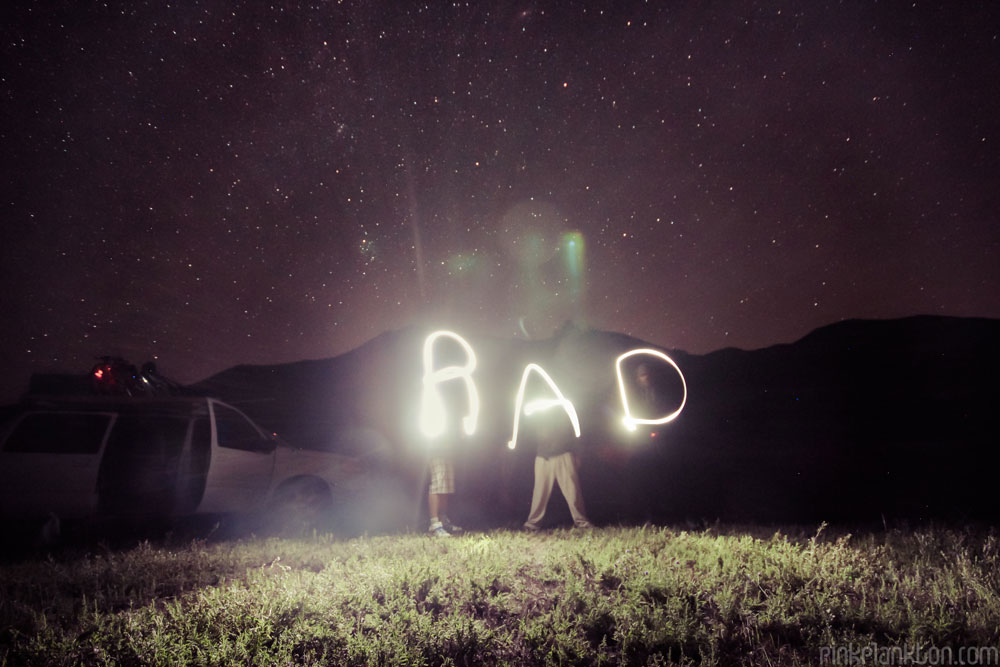

The last 5 days of the festival is when most of the indigenous tribes leave and the psytrance stage opens. Because of this, the vibe of the festival completely changes. By this point, I was feeling much happier. The next few days would be spent capturing more b-roll, my POV shots, and a few time-lapses. I was feeling confident about being able to present both sides of the story with the interviews I had collected.

Two days before the festival ended, I took my first entire day off. I spent it in the forest with good company, and then danced until sunrise (my favorite part of any festival). I’m very grateful for all the friends I met that reminded me why I love these events and this community so much - because of the people.

Final Thoughts

Filming this documentary was an emotional rollercoaster. It was the most challenging project I’ve ever worked on to date, but I am very happy with the outcome and so glad to have finally achieved a goal that I’ve had for so long. I learned a lot about documentary film making and storytelling. I was forced to question the community that I love so deeply.

Most importantly, I learned a lot about myself. Living in the jungle, isolated from normal society, for almost 3 weeks, will change anyone. But being faced with the additional challenge of filming this documentary in a festival environment, all alone, was a difficult experience that forced me to think harder, envision stronger, focus deeper, and grow much more than I ever thought possible.

So much yoga...

So much yoga...

The ocean floor creates a giant mirror, awesome for photos

The ocean floor creates a giant mirror, awesome for photos

This girl was also an awesome dancer

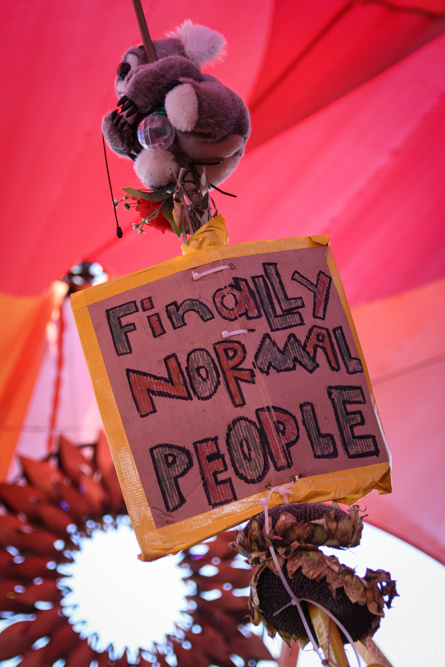

This girl was also an awesome dancer The other side of this sign reads, "we dance." You really do feel like family by the end, united by your love for music but also united by the experience, the connections, the learning, and the growing.

The other side of this sign reads, "we dance." You really do feel like family by the end, united by your love for music but also united by the experience, the connections, the learning, and the growing.